|

6/29/2014 Safe Housing for Trafficking Survivors By Alexis Keyworth, See the Triumph Guest Blogger

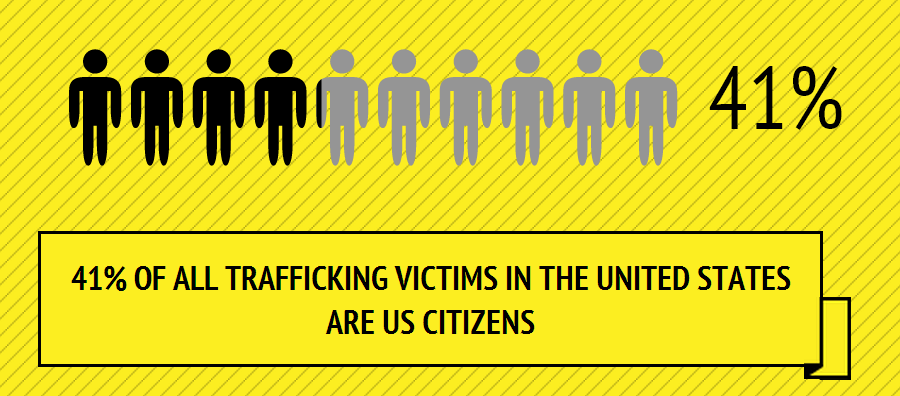

Housing for victims of human trafficking is sparse. In the United States, we claim to have about 200 safe houses, which may have just a few beds, each. Compared to the number of victims we have, which is somewhere in the hundreds of thousands, this is basically a Band-Aid on a broken bone. Victims are more vulnerable when they truly believe they have no way of escaping. Throughout their experience while being trafficked, they are probably told about how nobody will believe them if they escape, or that nobody will care, or how there isn’t any where for them to go because their trafficker is going to find them, or their family and somebody will end up paying. The sad thing is, they’re right - about part of it, anyway. There usually isn’t a great answer as to where the victim can go to receive services and the care they deserve. Going to a homeless shelter could get them killed, without the proper protections and confidentiality in place. If they end up at a women’s shelter, they will be surrounded by people who have experienced different types of abuse then they have. Although domestic violence is similar to human trafficking in some ways, there are also huge differences. Trafficking victims often find solace while surrounded by people who have survived the same horrors, or similar ones, to themselves. Therefore, shelter specific to trafficked victims is very important to their recovery. As with domestic violence victims, it is quite important that we provide shelters that are protected and not easily identified. They must have strict confidentiality policies and be very careful about concealing the location from the public. A huge piece that is missing from the conversation is the lack of guidelines and regulations for housing victims of human trafficking. In North Carolina, there is no procedure or policy stating the rules for opening a safe house. All that is required is that you either follow procedures for opening and licensing a home school or a residential child care facility. These licenses do not address the need for counseling, or the danger of being discovered by the trafficker. Another piece hit me when I started learning about safe housing in North Carolina: every single safe house in the state has a religious background. Although this is by no means a horrible thing, there is a down side. The part that worries me is the stigma the victims may worry about if they were to enter a religious agency. After being forced to sell their bodies 10, 20, 30 times a day for sex, they might not exactly see where religion fits into their lives. Although religion may be a healing tool for some, others may feel out of place. With regulations, there will be more safe houses opened that do not have religious ties and are more welcoming to non-religious victims. Also, we will be able to better ensure the recovery, safety, happiness, and future success, specifically for victims of trafficking. Therefore, what we really need to talk about is the need for policy at the federal and state levels that addresses this need, as well as a protocol from start-to-finish for human trafficking cases. Alexis Keyworth is a student at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. By Kiricka Yarbough-Smith and Roxy Logan Q: What exactly is human trafficking? Is it the same as the smuggling people across a border? A: There are some commonalities between smuggling and trafficking, but the two are very different. Smugglers are typically paid to transport a person who wants to go across the border.Human trafficking involves exploiting a person as a commodity—with or without crossing any borders at all. It is true that with both international trafficking and human smuggling, there are usually “push” factors (problems in a person’s home country that make them want to leave) and “pull” factors (those that lead people to want to work in another country).These can drive people to travel, which then puts them at risk for exploitation from unscrupulous smugglers or traffickers, who may lie, charge outrageous fees for transportation, or even take their identity documents. So these two issues are similar in that they both can involve concealing people and taking them across national borders. But trafficking does not always involve these things, and, under national and international laws, it always involves more. Trafficking does not require anyone to cross a border. It can happen within a single city, state or country (this is “domestic” trafficking). It also involves force, fraud, coercion, or an underage victim, whose labor or body is sold for others’ profit. People may pay and consent to being smuggled across the border, then live in the new country as free individuals. Meanwhile, human trafficking victims are enslaved, often within their home countries, and do not truly choose to be trafficked. Q: Isn’t it just young girls and women who are trafficked? A: There is no one group that is trafficked, although some groups are targeted and exploited more often than others. Males and females of all ages, nationalities, ethnicities, and races are trafficked within and across countries for sex, labor, or both. Stories involving young women being sex trafficked often receive the most media coverage and public outrage, but trafficking is a crime that can reach the most vulnerable individuals in any group. In fact, both boys and girls are victimized through labor trafficking, domestic servitude, and sex trafficking for acts of prostitutionor child pornography. Both adult men and women are also trafficked, and adult men are even more likely than women to be trafficked for labor. Q: Isn’t human trafficking just a problem in other countries? Human trafficking is here in the United States, in every state. When advocates first started detecting human trafficking cases, they often involved victims from other countries. These victims were more likely to stand out and, therefore, be reported. Also, it was often more obvious that victims from other countries really were victims; advocates and law enforcement could see that abused people unfamiliar with our language who were brought here from other countries were indeed “victims” who could not be expected to ask for help or choose to leave their traffickers. Today, we know that most human trafficking is actually “domestic”—within our own country, involving our own residents as victims, buyers and sellers. These victims may know our language and technically be able to get back home, but they are so abused and brainwashed that they, too, are victims who cannot simply leave. Human trafficking is a global epidemic that preys on individual vulnerabilities, such as poverty, and is driven by the demand for trafficked labor and sex. These problems persist in virtually every nation in the world, including our own. Like these other nations, the U.S. has extensive work to do in order to address the things that drive its trafficking epidemic.  Kiricka Yarbough Smith provides training and technical assistance to service providers as well as resources and referrals to survivors of human trafficking. She also serves on the Executive Committee of The NC Coalition against Human Trafficking (NCCAHT) and co-chairs the NCCAHT committee to develop and implement Human Trafficking Rapid Response Teams across the state. She is also a member of Partner’s Against the Trafficking of Humans. Kiricka currently serves as a faculty member for the US Department of Justice Office on Violence against Women and Futures Without Violence project, building collaboration to address trafficking in domestic violence and sexual assault cases. She has also partnered with the Children Advocacy Centers of NC to develop and implement a domestic minor sex trafficking curriculum. Roxy Logan is an anti-trafficking activist, writer, and attorney. She currently serves as a board member and fundraising committee chair for the Rape Crisis Volunteers of Cumberland County. Previously, she assisted the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault with their human trafficking efforts. She earned her B.S. (magna cum laude) in Political Science from the University of Southern California, and her J.D. (cum laude) from William & Mary Law School. By Kiricka Yarbough-Smith and Roxy Logan The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) recommends a four-pronged approach to addressing human trafficking: Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, and Partnership. Unfortunately, prevention is often an underfunded and underutilized tool in the fight against trafficking. Resource-strapped organizations, both public and private, are often restricted to reacting to trafficking cases rather than undertaking more systematic efforts to prevent future suffering and exploitation. To prevent trafficking, our movement must find innovative, low-resource, credible means of (1) addressing the emotional and material vulnerabilities of children most at risk for being trafficked and (2) confronting the cultural messages about masculinity and sexuality that drive willingness to sell or buy trafficked individuals. Educating populations vulnerable to trafficking is a critical component of prevention. Effective prevention programs should educate and provide outreach to particularly vulnerable populations of children to help combat the negative cultural and emotional forces that place them at increased risk for commercial sexual exploitation. This programming should help combat negative images children receive about sexuality from adults and the media, as well as focus on how to develop positive self-images and age-appropriate, healthy views of gender roles and sexuality. This programming is suitable for all demographic groups. Another technique some advocates have found useful is to reach out to the most vulnerable girls about the realities of prostitution and the techniques that traffickers might use to recruit them. Many trafficker-pimps initially portray sex work as a glamorous, easy way to make money and to earn the love and approval of the pimp. Traffickers carefully craft messages to lure in individuals based on their vulnerabilities, from the hopelessness engendered by multi-generational poverty to a basic desire for love. Programming must include a reality check for vulnerable young people on what the life traffickers offer really entails. Survivor-led programming here is likely to be the most effective, as youth are not always ready to listen to adults’ seemingly abstract admonitions about good long-term decisions. Because many pimps exploit children’s vulnerabilities by posing as loving boyfriends, caretakers, or a surrogate family, prevention curricula also needs to teach previously abused or neglected girls to develop a healthy understanding of love that is free of abuse and exploitation. These programs are especially important for the most vulnerable demographics, such as urban low-income youth most likely to be targeted because of their lack of economic options and foster care children who may never have known what a healthy, loving family life is like. It is important to offer after-school programs and hope for a better life to populations vulnerable to involvement in trafficking, whether as perpetrators or victims. Some advocacy groups have recently begun to offer resources for mentorships, internships, and constructive after-school activities that build self-esteem and offer legal, non-exploitative paths to financial and life success. To get the word out about such programs, advocates can offer materials and small group sessions to parents or youths in a targeted area. Depending on resources available, groups can also plan large-scale public events that bring in audiences through fun offerings, then give groups access to parents and youth who can use these resources. Any single group can only reach a limited number of youth state-wide, so it is important for both large, top-down and smaller grassroots groups to collaborate to expand the reach of prevention efforts. To accomplish this, advocates can offer leadership programs that train youth to become effective movement leaders and advocates in their own communities. Larger groups not performing direct services and outreach can support these programs by offering logistical training to help existing agencies around the state to train and engage youth. Community volunteers may also help expand the movement’s real reach, as well as link vulnerable groups to a wider variety of community resources. To help expand community members’ involvement, groups may find it helpful to enlist and train volunteers from numerous disciplines to help expand prevention work into more workplaces and organizations. To prevent trafficking, we must also address the availability and demand for trafficked people. The majority of sex traffickers and purchasers are male, so educating men and boys is essential to preventing trafficking. Organizations should work to reduce male participation in sex trafficking and similar forms of gender-based oppression by addressing unhealthy norms about gender-based dominance and instilling healthy, respectful models of masculinity. Challenging damaging views of gender and sexuality is critical to addressing demand. The women’s movement has made major gains in addressing women’s equality, but today we are losing traction on developing a healthy, egalitarian sexual culture. Today, media from pornography to music videos often provides a haven for an anti-women backlash, in which gender roles are clear and regressive. To reduce demand, we must offer more positive forms of education about healthy sexuality and openly confront the negative messaging about gender and sexuality that normalizes the sale and purchase of women for sex. To increase credibility with young boys, it helps to involve male staff members and, where possible, male athletes (local or national), musicians, political or business leaders, or other examples of positive male role models. These men can mentor boys on positive masculine identities and even work with athletic coaches to change the common terminology that devalues girls and reinforces links between sexuality, dominance, and aggression. The anti-trafficking movement’s prevention work must involve men in changing other men’s attitudes about commercial sex, respect for women as equals, and the meaning of healthy masculinity in our generation and those to come.  Kiricka Yarbough Smith provides training and technical assistance to service providers as well as resources and referrals to survivors of human trafficking. She also serves on the Executive Committee of The NC Coalition against Human Trafficking (NCCAHT) and co-chairs the NCCAHT committee to develop and implement Human Trafficking Rapid Response Teams across the state. She is also a member of Partner’s Against the Trafficking of Humans. Kiricka currently serves as a faculty member for the US Department of Justice Office on Violence against Women and Futures Without Violence project, building collaboration to address trafficking in domestic violence and sexual assault cases. She has also partnered with the Children Advocacy Centers of NC to develop and implement a domestic minor sex trafficking curriculum. Roxy Logan is an anti-trafficking activist, writer, and attorney. She currently serves as a board member and fundraising committee chair for the Rape Crisis Volunteers of Cumberland County. Previously, she assisted the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault with their human trafficking efforts. She earned her B.S. (magna cum laude) in Political Science from the University of Southern California, and her J.D. (cum laude) from William & Mary Law School. 6/26/2014 What Is the Face of Human Trafficking? By Rachel Parker, See the Triumph Guest Blogger

Heartbreaking, frustrating, bizarre, and miraculous…working with survivors of human trafficking are all of these things and more. Definitions and statistics are needed to move systems and infrastructure forward, but in moving a community to be concerned for their fellow man, for their neighbor, it should be the knowledge that as little as one has been affected. Human trafficking at its heart is termed best by Lauren Bethell in that it is an exploitation of vulnerability that makes a person the commodity. If you accept this as being so, then consider who you think to be vulnerable…have you ever been vulnerable? Struggled with self-esteem, relationships, dreams, and/or finances? We continually see the victim as someone other than ourselves or our family, but they are people too, someone’s family, with dreams and goals and visions of an exciting life. They are not to be pitied or labeled; trafficking is a crime that was perpetrated against them, but does not define who they are. They are survivors and we should not forget that. From a boy struggling to become a young man who wants to protect the innocent and become … a soldier. From a woman who is hurt by the services and people around her that should protect her but fail, leading her to flee and seek protection elsewhere but finds that it is corrupted. To a woman struggling with identity and looking to rely on the goodness of those around her, but finding that it falls short too often. And a parent that sells their child. The situations change, the victimization labor trafficking and/or sex trafficking, and the needs may vary, but a person remains who has a life ahead of them. Aftercare services are developed to help meet emergency, transitional, and long-term needs. This can be housing, medical, dental, mental health, education, employment, interpretation, transportation, and legal assistance. These services should maximize their strengths, and goals set by the survivor with the service provider. The results can be miraculous… From a woman learning self-defense and situational awareness so that she will not be hurt again. From a woman getting a new job and buying her first car. To a woman learning about the role of service provision and assistance for individuals and the community resulting in the birth of a new advocate and humanitarian. And a man learning to work through a disability and finding joy in expression through art. Rebuilding a life is a painful, up-hill battle, and is expensive. It is also something that the community needs to be involved in as this crime exists according to supply and demand. Where have we created the demand? Human trafficking exists in the distortion of our culture from what we perceive as our right and what is a luxury. TV ads, movies, magazines, and retail tell us all that it is our right to have that new product, electronic, chocolate, good time and ‘happy ending’, etc. We are a nation of consumers, and we think that it’s ok. That cheap sex and cheap goods are sought after as the norm. That we consume, attain, download, or ingest everything in one second and throw it all away in the next. Where is the value in this? We look at victims and our hearts break, but we don’t change the fact that we are the buyers that continue to push victimization of our fellow citizens, community members, friends, and loved ones. Heartbreaking, frustrating, and bizarre in considering the impact of human trafficking on a life and realizing that we as individuals and part of a community have been complicit, if unknowingly, in this victimization. However, moving forward you can no longer claim that it is unknowingly perpetrated on your part. Miraculous in seeing victims transition to survivors, and people coming together to support them in this transition. There is strength in everyone, how will you utilize yours? Rachel Parker is the Anti-Human Trafficking Specialist for World Relief High Point’s Anti-Human Trafficking Program. Rachel works to strengthen collaborative relationships with law enforcement, service providers, the church, and communities-at-large to serve and support victims of human trafficking. Rachel coordinates the Triad Rapid Response Team as well as monthly conference calls for the NC Rapid Response Team Coordinators. She also represents World Relief High Point on the Executive Board of the NC Coalition Against Human Trafficking (NCCAHT). By Sara Forcella, See the Triumph Contributor

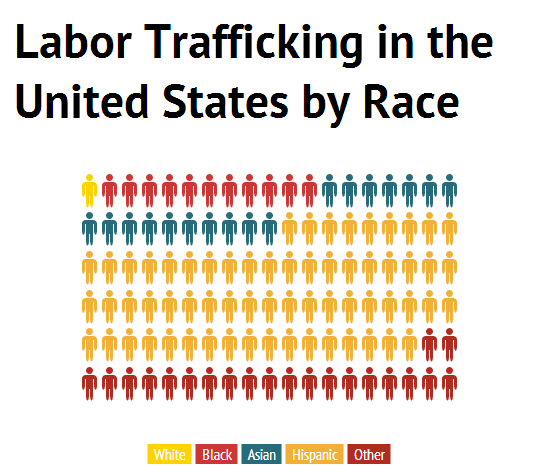

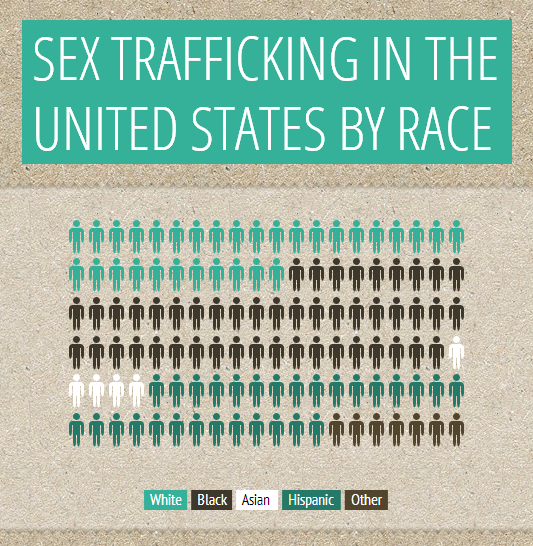

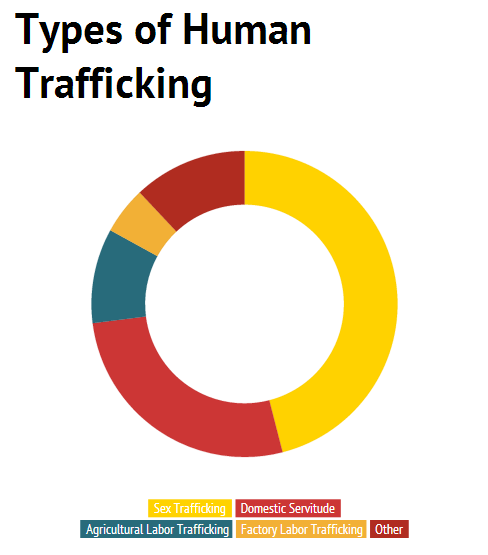

Sex trafficking is not something that is easily understood, or frequently discussed. Many times victims of sex trafficking, like victims of domestic violence, face being stigmatized by their communities and our society as a whole. As human beings, it is common for us to attempt to categorize people and place them into boxes. By doing so, we are able to quickly understand and label others, to distinguish whether or not we like them, and decide how we interact with them. The problem with these labels, however, is that they allow for clouded judgment and misunderstanding instead of tolerance, compassion, and understanding. It’s common for us to put victims of sex trafficking in very rigid and unkind boxes--within our society they may be viewed as willing prostitutes or even undocumented citizens attempting to gain citizenship--all of these accusations are false. Most victims of sex trafficking are unwilling workers who are forced to work, abused, and threatened. Victims of sex trafficking may find their way into this “business” for many different reasons. In some cases children or teens are kidnapped and forced into the industry. Runaways and those living on the streets also face being lured into the sex trafficking industry. Some victims may be tricked or coerced into the industry with promises of wealth or a better life. One thing to remember about the sex trafficking industry is that it relies on members of vulnerable populations to fulfill its needs. Traffickers may target women and children because of their disenfranchised place within society. Immigrants and undocumented citizens may also be targets due to their limited access to resources. Traffickers are tactful and understand that by using lies, manipulation and false hope, they are sometimes able to coerce people into their work. While it is true that human trafficking can take place in legitimate business settings, victims typically will not seek immediate help. Many times victims of sex trafficking face depression, self-blame, and trust issues. Victims may be scared of what will happen to them if they do turn to others for help. Just because somebody does not turn to you for help does not mean that they do not want help, or need help. Before you make snap judgments about those working in the sex industry, remember that a majority of victims do not willingly chose to be part of it. It is up to us to end the stigma that is attached to sex trafficking. By breaking down the boxes that we created and the labels we attach, we are taking a small step to change the way that victims of sex trafficking are seen within our society. 6/22/2014 Understanding Human TraffickingThe same great group of students who brought us this Human Trafficking Awareness Video have created the infographics below to help illustrate the impact of trafficking. The sources they used for the statistics include the following:

|

Archives

July 2024

CategoriesAll About Intimate Partner Violence About Intimate Partner Violence Advocacy Ambassadors Children Churches College Campuses Cultural Issues Domestic Violence Awareness Month Financial Recovery How To Help A Friend Human Rights Human-rights Immigrants International Media Overcoming Past Abuse Overcoming-past-abuse Parenting Prevention Resources For Survivors Safe Relationships Following Abuse Schools Selfcare Self-care Sexual Assault Sexuality Social Justice Social-justice Stigma Supporting Survivors Survivor Quotes Survivor-quotes Survivor Stories Teen Dating Violence Trafficking Transformative-approaches |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed