|

By Sara Forcella, See the Triumph Contributor

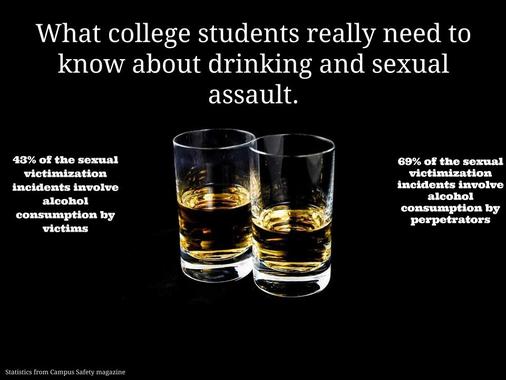

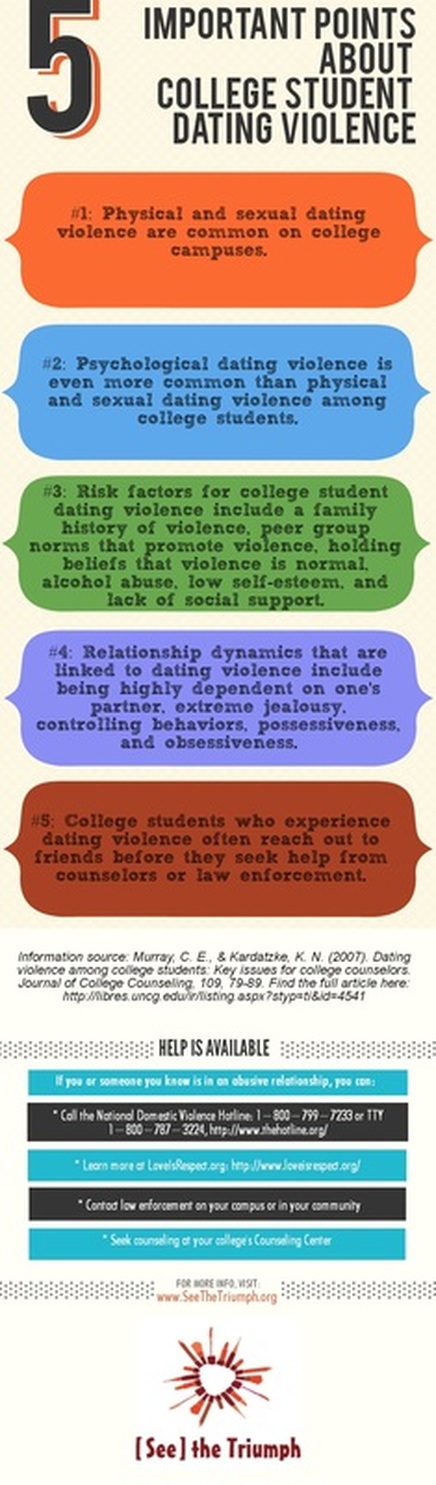

College is a time of vast change for young adults. It is also a time of many firsts, which could involve your first time living on your own, first time having a roommate, first time taking college-level courses, first committed romantic relationship, and possibly first time drinking alcohol. While not all students on college campuses drink, many do. College culture as a whole is affected largely by the influence of alcohol and the sense of comradery that occurs among students who live together on campus. However, alcohol also inhibits students' decision making skills. Therefore, as a sexual violence prevention educator, I believe that ignoring the amount of drinking that takes place on college campuses is not only counterproductive, it's downright dangerous! The danger of ignoring students’ use of alcohol lies not only within the alcohol drinking alone, but its connection to sexual assault. On college campuses, perpetrators of sexual assault use the consumption of alcohol as a tool to reduce their victims’ decision making and motor skills. It’s important to note that alcohol is not the cause of sexual assault on college campuses--the perpetrators themselves are the only ones to blame. Nevertheless, the use of this drug to inhibit victims is clearly identifiable. Consider this: research shows that as many as 90% of all rapes on college campuses occur when either the perpetrator or victim was using alcohol (Brown University, Health Promotions). Where does this statistic leave parents, educators, and students? Does it mean that we don’t send our children off to college? Or that even college students over the age of 21 shouldn’t be allowed to drink? Neither of these seem to be the answer--but what is? For me, the answer lies in education. Just like with any other health concern, we must educate students about sexual assault before they attend college and again while they are on campus. Research shows that women in late adolescence to early adulthood are at the highest risk of being sexually assaulted. Therefore, we must educate young women that sexual assault is a daily risk, with or without the consumption of alcohol, especially for those between the ages of 18 and 24 (Collins & Messerschmidt, 1993). Furthermore, when alcohol is added to the equation, women are even more at risk for being sexually assaulted. Most importantly though, we need to educate women that sexual assault is never okay and that it is never their fault. But we can’t stop there! We can’t just educate half of the population and make it their responsibility to fend off criminals. Research also shows that most perpetrators of sexual assault are men (Sedgwick, 2006). Instead of victim blaming, lets hold the perpetrators accountable! We need to teach them that just because a partner has agreed to some level of intimacy, it does not mean they are entitled to take it farther, and that if they do so without permission, it’s sexual assault. They should know that getting sex by using coercion and manipulation are in fact forms of sexual assault. Men need to understand that feeding someone drinks in order to make obtaining sex easier is sexual assault. It’s our responsibility to teach men to look for ‘enthusiastic consent’ before engaging in sexual activity, instead of acting upon a lack of a ‘no.’ Finally, men need to face the reality that if somebody reports that they were sexually assaulted while drunk, it can not only change their own lives, but also that survivor’s life. It’s not only women who are affected by sexual assault on campus, men are too. Women, like men, can be perpetrators of sexual assault. It’s our responsibility to teach both men and women (beginning at a young age) to understand personal boundaries. This means asking for consent before engaging in any kind of intimate act, whether it be as silly as tickling or as serious as sex. When it comes to alcohol, both men and women need to know that if either party is intoxicated that they can not legally give consent. Alcohol has the potential to change things, and it only takes a matter of seconds to violate, shame, degrade and sexually assault someone--therefore before these things are ever able to happen, let’s take the time to educate our young adults.

3 Comments

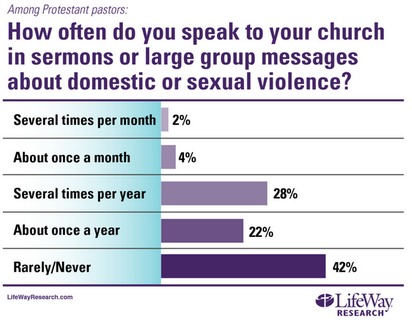

By The Spiritual Alliance to Stop Intimate Violence Broken. Silence. Broken. Silence. These words mean a great deal to survivors of intimate abuse. SAIV and our partners would like to see domestic violence included as a component of all theological education. A new poll of 1,000 pastors shows clearly that pastors often fail to address domestic and sexual violence appropriately. They consider themselves ill-equipped to respond to incidents of violence. The following is taken from the Huffington Post article of June 2014 on this subject, entitled, “Pastors Rarely Preach About Domestic Violence Even Though It Affects Countless Americans.” Co-sponsored by the Christian nonprofits, Sojourners and IMA World Health, the survey also found that pastors were more likely to believe domestic violence was an issue in their community (72%) than an issue in their church (25%). “I think many pastors still don’t think it exists in their congregation,” Yvonne DeVaughn, director of Advocacy for Victims of Abuse (AVA), told LifeWay.

Violence against women was named as a “significant public health issue” by the World Health Organization in 2013, which reported that 35 percent of women around the globe have experienced sexual or physical abuse by a partner or non-partner. And according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the chance of a man experiencing abuse at the hand of an intimate partner was one in four. What makes this poll unique is that there is not much data on how pastors view and address the issues of domestic and sexual violence. According to Rick Santos, President and CEO of IMA World Health, “there is little information out there about what is actually happening in the U.S. faith community on this issue.” Despite the poll’s major finding — that pastors underestimate the pervasiveness of sexual and domestic violence in their congregations — the report offers some hope. Of the pastors polled, 81 percent reported that they would “take appropriate action to reduce sexual and domestic violence if they had the training and resources to do so.” Sojourners recently published I Believe You: Sexual Violence and the Church , a study edited by its president and founder, Jim Wallis, and Catherine Woodiwiss, Associate Web Editor. The study features three essays about women, sexual violence, and their experiences in dealing with their abuse in their churches. It is a step forward in the effort to bring light to an issue that is often cloaked in darkness and to give voices to victims who often feel silenced by the church’s failure to understand the prevalence of sexual and domestic violence. “This is a conversation the church needs to be having but isn’t,” Wallis said. “We cannot remain silent when our sisters and brothers live under the threat of violence in their homes and communities.” This post was adapted, with permission, from SAIV's original blog post on their web-site, which can be found here: http://saiv.org/broken-silence-a-call-for-churches-to-speak-out/. Learn more about SAIV here: http://saiv.org/about/. By Christine Murray, Kristine Lundgren, Gwen Hunnicutt, and Loreen Olson

Members of the Traumatic Brain Injury and Intimate Partner Violence Research Group at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro Note: This blog post is also being published on the Stop Abuse Campaign blog. You can find this post by clicking here. In recent weeks and months, the National Football League (NFL) has faced intense scrutiny over its handling of the Ray Rice domestic violence perpetration case. The case dominated the headlines as two separate videos emerged, showing first that Janay Rice was left unconscious by the assault in February, and second that Ray Rice delivered a powerful punch to her face that knocked her unconscious. The graphic video left many people reeling about the severity of the abuse, as well as the minimal repercussions that Rice faced initially. As an interdisciplinary group of researchers who study the risk of traumatic brain injury (TBI) among survivors of domestic violence, we watched those videos through a different lens. We saw an example of one of the many types of domestic violence that places the victim at risk of experiencing a TBI. We cannot comment directly on Janay Rice’s health, but the video depicts that she lost consciousness, and loss of consciousness is one of the symptoms associated with an injury to the brain. In fact, it is the first symptom listed in the NFL’s Head, Neck, and Spine Committee’s Protocols Regarding the Diagnosis and Management of Concussion. The NFL knows a lot about concussion, which is a mild form of TBI. In December 2013, the NFL donated $30 million to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund research on understanding and diagnosing TBI. This donation was made on the heels of a $765 million settlement that the NFL made in August 2013 with former players who sustained game-related injuries to the brain. Professional football players face a high risk for TBI. Current research--which the NFL does not dispute in recent court documents--suggests that as many as one-third of former players will experience one or more brain injuries with negative, often chronic health consequences. For at least two decades, the NFL has been studying and developing policies and protocols to prevent, identify, and respond to TBI among its players. As a result of these efforts, the league implemented rules designed to prevent TBI, such as banning the types of hits that are most likely to result in an injury. Furthermore, they adopted protocols that provide guidelines for examining injured players to determine the potential for TBI immediately following an injury, for managing symptoms, and for determining when players can return to play. Some of the major requirements of these protocols include that players who experience an injury which poses a risk for TBI must be assessed immediately, and if a brain injury is suspected, the player must be removed from the field right away, and then follow a detailed, phased process that involves daily monitoring in order to be gradually and safely reintroduced to game play. Any doubts that the NFL does not recognize fully the severity of TBI should be erased by the protocols’ stipulations that, during each game, each team is assigned an Unaffiliated Neurotrauma Consultant to provide an objective evaluation of potential TBI, and at each game there is a designated athletic trainer whose role is to watch the game from the stadium booth and be a spotter for potential TBI, using both direct observation of the game and video replay. Of course, the NFL’s policies and protocols regarding TBI address the actions of players on the field, and the NFL’s role and responsibility for protecting the safety and wellbeing of players’ relationship partners could be debated. However, the NFL is practicing a dangerous double standard when it takes the issue of TBI so seriously among its players, but ignores the harm of potential TBI resulting from a domestic violence event perpetrated by those same players. Based on the five steps in the NFL’s Return-to-Play Protocol following a diagnosed TBI, Ray Rice may have missed more games had he been the one knocked unconscious in the elevator, rather than the two games he was required to miss in accordance with his initial suspension from the NFL for knocking Janay Rice unconscious. Although there is growing recognition of the potential for TBI among survivors of abusive relationships, to date there has been relatively minimal attention to this issue in both research and practice related to domestic violence. However, current research suggests that as many as 30% to 74% of all victims of domestic violence who seek services from battered women’s shelters and emergency departments have a TBI (Kwako et al., 2011). Unlike other populations in which there is greater attention to the dangers of TBI--especially professional athletes--survivors of abusive relationships typically have far fewer resources and less immediate access to assessment and rehabilitation services when they experience a potential TBI. Furthermore, the cyclical nature of abusive relationships means that survivors who experience one TBI are at a greater risk of reinjury. Multiple TBIs place survivors at risk of even more serious physical and mental health consequences. The current dangerous double standard within the NFL regarding TBI experienced by players on the field and TBI resulting from a domestic violence incident underscores the need for more resources and cultural change--both within the NFL and in the general population--that will prevent further violence, provide support to survivors of abuse, and hold offenders accountable. As the NFL faces increased calls to work to prevent domestic violence among its players and take action when it occurs, one specific area in which the NFL can respond is by applying its vast resources and knowledge base surrounding TBI to improving resources for survivors of domestic violence who are at risk for sustaining this type of injury. Reference: Kwako, L. E., Glass, N., Campbell, J., Melvin, K. C., Barr, T., & Gill, J. M. (2011). Traumatic brain injury in intimate partner violence: A critical review of outcomes and measures. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12, 115-126. doi: 10.1177/1524838011404251 By Juliette Grimmett, See the Triumph Guest Blogger Founder, Chrysalis Network I cannot recall a Thanksgiving dinner that did not include me starting up a discussion about sexism and gender-based violence (GBV). There have been times where I facilitated activities on my parents kitchen chalkboard about how the use of problematic words like “bitch” and the pervasive, all-encompassing term “guys,” are dismissive of women and contributes to rape culture. I’ve explained that my partner and I encouraging our two young boys to wear whatever makes them happy, even if it is glittery shoes or pink-heart leggings, is a form of sexual violence prevention. And I’ve talked about how we must change our narrative surrounding GBV to focus on the perpetrator and not the survivor, such as shifting the question from “Why did s/he stay?” to “Why did s/he abuse her/him?” My beautiful and open-minded family listens, interacts respectfully, and often expresses gratitude for these talks. We all have different roles within our family and circle of friends. One of mine is to start conversations about challenging and uncomfortable issues, particularly with the people I know who do not do this work. I am mostly happy to have this role, though at times the pressure to start the conversations can be overwhelming. I wish that my daily conversations and thoughts about women’s safety and gender equality were also their norm. Over the past two years, as a result of pervasive media attention focused on sexual and dating violence, particularly on college campuses, I have felt a remarkable shift among my loved ones. They have tweeted and posted relevant articles on Facebook, referenced actual cases in our discussions, and my 75 year-old uncle called to tell me about the front-page article of the NY Times on campus sexual assault. People in my life are now creating space for these conversations, along with public figures like Diane Rehm from National Public Radio, John Stewart from the Daily Show, Brian Williams from NBC Nightly News, and perhaps most importantly, Vice-President Joe Biden and President Barack Obama. Of course GBV on college campuses is nothing new. My story of rape from almost 20 years ago is no different than the ones we hear about today. Further, countless women, people of color and members of LGBTQI communities have been talking about this violence for decades, demanding action and accountability. While those of us doing this work are frustrated with how long it has taken to get to this meaningful national dialogue, we are equally inspired that this shift has occurred within our lifetime. I think of how different the aftermath of my assault would have been if it happened today. Survivors voices are beginning to be respected and perpetrator accountability means suspension or expulsion, not social probation as it was in my case. Almost all of us have heard at least one story from the courageous survivors throughout the country who are holding their institutions of higher education accountable for mishandling their sexual assault, specifically as violations of Title IX. The White House (the White House!!) has launched a national campaign Not Alone that provides resource information on how to respond to and prevent sexual assault on college and university campuses and in our schools. We are also learning about the long-awaited Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act (Campus SaVE) signed into law in March 2013 as part of the Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization. Campus SaVE, designed as a companion to Title IX, was developed to increase transparency about the scope of sexual violence, guarantee survivors enhanced rights, provide standards for institutional conduct proceedings, and provide campus community wide prevention educational programming. Dating and domestic violence and stalking are clearly identified as components of sexual violence in Campus SaVE, which had been unclear in Title IX. Additionally, Campus SaVE currently defines primary prevention programs as: “programming, initiatives, and strategies informed by research that are intended to stop dating violence, domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking before they occur through the promotion of positive and healthy behaviors and beliefs that foster healthy, mutually respectful relationships and sexuality, encourage safe bystander intervention, and seek to change behavior and social norms in healthy and safe directions.” Primary prevention of sexual violence requires us to fundamentally change the responsibility narrative from survivor behavior to perpetrator and community accountability. Consider the different message that is conveyed in headlines that read “18 year-old college student was raped” compared to “18 year-old college student committed rape.” When the norm changes to make violent behavior and perpetrator accountability the subjects of the discussion, we move forward in ending rape culture. I hope that primary prevention messages will shift our conversations away from casual victim-blaming interrogations of “What was she thinking wearing that?” “Why didn’t she use her pepper spray?” “Why didn’t she watch her drink?” and the soon to be, “She should have used that rape-drug detecting nail polish.” The new survivor supportive and community engaged norm would ask questions that advance positive cultural change such as “Why did that person choose to rape?” “Why do men feel entitled to degrade and abuse women’s bodies?” “How can we redefine masculinity to include love, respect and empathy?” “How can we stop perpetrators from perpetrating?” The present national dialogue and related possibilities are unprecedented. It helps to change how our culture understands GBV. I believe it would be hard to find a first-year college student who has not heard something about campus sexual assault before coming to college this year. In addition, Campus SaVE requires that campuses educate incoming students on sexual violence prevention strategies, resources, policies (including a definition of consent), and laws. If done correctly, a campus culture is fostered in which survivors are supported, resources for help are clear, and the message of accountability is strong. With institutional structures in place, campus spaces are created in which survivors feel they will be believed and supported and may be more likely to report the abuse they experience. Presently, there is an active national community of campus survivors committed to holding campuses accountable. One tool developed by these activists is the website Know Your IX, a campaign that aims to educate all college students in the U.S. about their rights under Title IX. As survivor Annie Clark shared at a May 2013 press conference, “victims of sexual violence have reached a critical mass where we can no longer be ignored.” While I am excited about the current climate, I remain guarded. We can require campuses to do all sorts of things, however the real test of success will be when value statements and institutional policies are aligned. Certain questions of commitment, adaptability, and sustainability remain. Will resources for survivors be safe for our LGBTQI community members, male survivors, and people of color? Will encouragement to report incidents be matched with a sensitive and understanding responder? Will the campus do the bare minimum or will they invest significant resources into effective, accessible and comprehensive prevention and response programs? Still, I remain encouraged as I know change has come because my uncle called me. I know change has come because of all the “likes” on my Facebook posts about these issues. I know change has come because this year, on my birthday, I heard this: “Perhaps most important, we need to keep saying to anyone out there who has ever been assaulted; you are not alone. We have your back. I’ve got your back.” - Barack Obama, January 22, 2014 You are not alone. You are believed. It is not your fault. Tell someone. Juliette has over nineteen years of professional experience working with communities, schools, and college and university campuses. During this time she has provided education and training to students, faculty, and staff on issues concerning sexual and dating violence prevention, advocacy, policy, and activism. Her past 10 years have focused on creating and implementing violence prevention and response programs on various college campuses including the University of South Carolina, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and most recently, NC State University where she was the Assistant Director of the Women’s Center. She served two terms on the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault’s Board of Directors as the Campus Representative, and chaired the Legislative and Development Committees. She currently serves as an appointed member of the NC Sexual Violence Prevention Team as well as the Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancements and Leadership through Alliances (DELTA) team. Juliette grew up in Newton, Massachusetts and France, loves the Boston Red Sox, feminism, and being an activist. Most of all, she adores spending time with her two young sons Harper and Sky and her partner, Marc who teaches her to always lead with love.

98.7 Simon FM Radio in North Carolina recently interviewed See the Triumph co-founder, Christine Murray, for a story on domestic violence. Check out the interview below!

By Christine Murray, See the Triumph Co-Founder

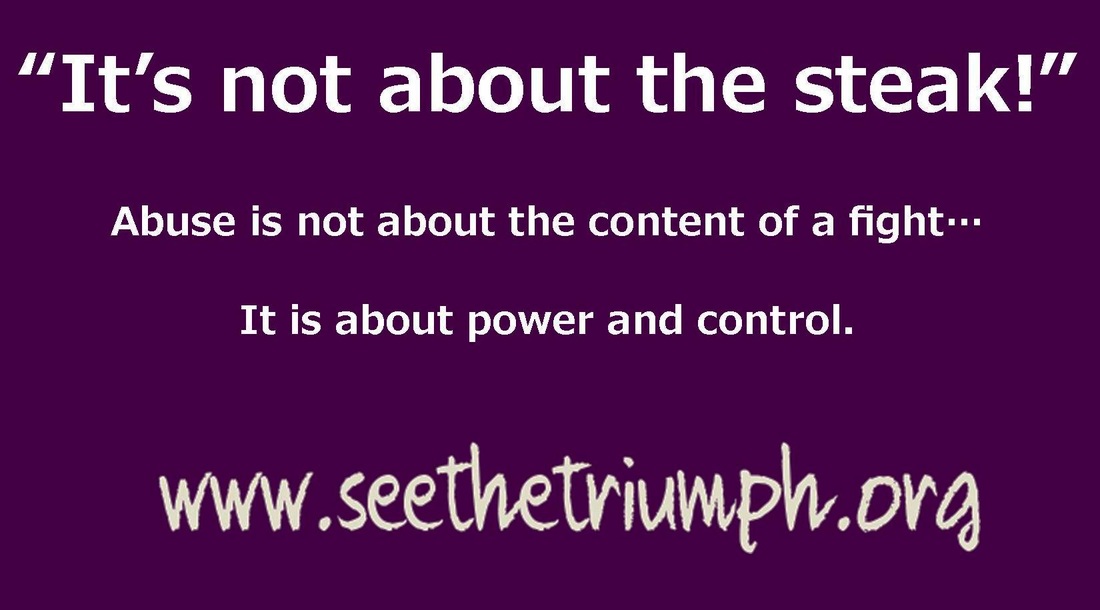

One of my simple pleasures in life is reading the newspaper every morning. I love getting up to date about the news of the day, learning about events and happenings in my community and beyond, and getting a daily dose of information about the important issues happening in the world around us. And yet, there are times when my daily newspaper reading turns into disappointment, frustration, and anger over upsetting news about injustices in the world around us. As one who cares deeply about ending intimate partner violence, some of my biggest frustrations come up when reading the paper and seeing stories about new cases of domestic violence. Every new story simply breaks my heart, because I believe that every person has a right to safe and healthy relationships. Beyond my frustrations when I read about cases of domestic violence, I, like many professionals who work to address domestic violence, get frustrated by the way that this issue is often covered in the media. For example, I remember one morning a few years ago reading about a man who had beat his female partner, which the newspaper stated happened because she didn’t cook his steak the way he liked it. If you could have read my mind at the moment I read that, you would have heard it screaming, “It’s not about the steak!!!!!!!!” In my view, the reason that man beat his partner had nothing to do with the way she cooked his steak, and it had everything to do with power and control. If you think that this story about the steak is an isolated incident, think again. Check out these examples of other “reasons” that media outlets gave for incidents of violence in the past month or so. I’ve bolded the alleged reasons for the violence in the list below:

It’s natural for people to want to try and explain why violence occurs. And, reporters have a responsibility to state the known facts of the stories they report. However, reporting overly simplistic reasons for abuse is problematic for at least two important reasons. First, by trying to identify these situational causes of domestic violence incidents, reporters trivialize the violence and inadvertently misinform readers about the dynamics of abusive relationships. By confusing the real reason that abuse occurs--because one partner is trying to control the other--the wrong message gets sent to the community and perpetuates the stereotype that domestic violence occurs as a result of a unique fight or one person’s inability to manage his or her anger. Second, by reporting on victims’ actions before a violent incident occurred, media stories imply that the victim may somehow have been to blame for the violence they experienced. These stories suggest that, had the victims just cooked the steak properly, not asked to use the bathroom on a long car ride, or not ate the fried chicken leftovers, the violence would not have occurred. Professionals who work to address domestic violence know, however, that the violence almost certainly still would have occurred, there just would have been a different triggering incident that set it off. Again, the abuse is not about the content of a fight...it is about power and control. Of course, we need ongoing media coverage about the issue of domestic violence to continue to raise awareness in the community and demonstrate the scope of the problem. But what if, instead of saying that violence occurred because of the specific incident that triggered the reported act of violence, reporters used language like the following: “The perpetrator hurt the victim because they were trying to hold power over their partner”? Now, I recognize that this is probably an overly idealistic vision for how the media will report cases of domestic violence. However, in order to fully end the stigma surrounding intimate partner violence, it’s important for the media to report on these cases responsibly. Such responsible reporting will help to educate the public about the issue and accurately depict the dynamics of abusive relationships. |

Archives

July 2024

CategoriesAll About Intimate Partner Violence About Intimate Partner Violence Advocacy Ambassadors Children Churches College Campuses Cultural Issues Domestic Violence Awareness Month Financial Recovery How To Help A Friend Human Rights Human-rights Immigrants International Media Overcoming Past Abuse Overcoming-past-abuse Parenting Prevention Resources For Survivors Safe Relationships Following Abuse Schools Selfcare Self-care Sexual Assault Sexuality Social Justice Social-justice Stigma Supporting Survivors Survivor Quotes Survivor-quotes Survivor Stories Teen Dating Violence Trafficking Transformative-approaches |

||||||||||||

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed