|

9/29/2016 Together In TriumphBy Jessica, See the Triumph Contributor

Moving through different countries during my twenties, I was consistently drawn to groups of women that had a community strength about them - the ones where you are welcomed in as a daughter or a sister, called “my dear” in the mother tongue, and taught to make the traditional family meal. My eyes were also drawn to the subtle signs of injustices occurring towards women in these cities, towns, and villages. Whether it was remnants of forced sex work, the whispers of familial violence, or the shadows of sexual abuse, the traces of women’s stories and their survival were there. These issues flew under the radar, quashed by cultural traditions, deep-seated gender imbalances, and biased solutions. As a survivor, I am accustomed to violence against women being interpreted as an uncomfortable topic. If a story comes up, the breath is taken out of the conversation. In media, favor is given to the abuser while we pick away at the survivor’s story, accusing them of everything but being a victim. As a world citizen, I am bombarded by tales of pain and sadness and at the end of each day, it can often seem the world is hopeless, that there is no way to help, and we see anything but triumph. But if there is anything I’ve learned from the women I’ve met and the stories I’ve heard, it’s that triumph is everywhere - and it is a beautiful thing to behold. Triumph might resound like an echo between two mountains, or be quiet like the flutter of butterflies’ wings among the garden flowers. Triumph grows in kitchens with lovingly-made meals that carry with them a long legacy of women healing and surviving with each other. Triumph flourishes on the living room floor, connecting and laughing together with knees folded on bright cushions, and sparks during intimate conversations with a friend who says “I believe you” and takes your hand. Triumph is in the satisfaction of doing something she wasn't allowed to and no longer feeling the anxiety and shame. Triumph is the justice found in custody battles and the journalist who gets it right. We see triumph alive on the Internet with community forums and in comments and posts on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, where girls and women of all nationalities find their common threads and rally together. Behind closed doors around the globe are girls and women of lioness strength, steadfastly navigating what it means to survive and triumph over violence; seeing the triumph is happening every day and everywhere in communities of women, big and small, that band together and say “no more” for each other. Triumph is survivors taking on the world in their own way, as it means to them, surrounded by a global community that understands and sees the triumph with her. No matter who we are, we can choose to see no hope, or we too can choose to see the triumph. 9/27/2016 A Story of Dating Violence in TurkeyBy Ezgi Toplu Demirtaş, See the Triumph International Ambassador

As a form of dating violence, psychological violence, is least known and visible, but most prevalent. To illustrate the dynamics of dating violence in Turkey, what follows is a story of love that turned into a story of violence in less than a year. This story one Turkish dating violence survivors’ illustrates some unique local factors in dealing with dating violence. The words of this survivor, who is a female college student in her early 20s, are as follows: “The relationship was exciting, passionate, fascinating…to begin with. He told me what to wear or not. I thought he was raised in a more conservative region, and he was jealous of me. He then interfered with the way I talk to the other people and controlled my social media accounts, such as ‘Who’s this guy, and where do you know him from? I am deleting him on FB.’ “We were constantly arguing the jealousy issues. He made me think that I should be a better partner. It was all about me, not him. I was his first partner, but he was not mine. This was another problematic issue. He continuously was talking about my previous relationships, which made me further feel guilty. Why wasn’t I his first? If I had been his first, then we would have a great, problem-free relationship. I and my previous relationships were to blame. “I still had some self esteem before he criticized my appearance and belittled me in front of others. I thought he was just kidding, but it hurt. I now know that I am beautiful, tall, and with looks that are very rare in this country. But it was not enough to him. “Then, I realized that I was so alone with no friends, because he had all of my time. We were doing everything together, and he tried to stop me from seeing my friends. I had no one to share except him. I had no choice to go to social events, because there were men there, and he thought they were all potential partners. He then went further and forced me to wear a hijab because his family was conservative and religious, and they wouldn’t accept me without it, even he does. He was from conservative city, and I was from a more liberal city. “Furthermore, he wanted me to appreciate him because he was spending all his time with me. I was becoming more and more unhappy, fragile, and less tolerant. We were arguing all the time. He was swearing, insulting, and ridiculing me. He slapped me a few times, but I told nobody because they would tell me to leave. He always was saying that he had a hard life and needed me. I felt guilty when I thought about leaving the relationship. I was cruel, according to him. I stopped wearing makeup and being stylish. “Then I read an article about dating violence. I became aware that I was a victim of dating violence. I cried a lot. I cried a lot that moment. The reason was not the violence. I asked myself why I allowed him to do all these things to me. I tried to leave a few times, but every time, he promised me to change and fix himself, and I turned back. “Now I think that he turned back because I was alone. At the time, I thought, ‘He made me like I am, an ugly, alone women. I can do nothing without him. Nobody would love me like him.’ My first efforts to leave were unsuccessful, but I did not give up. “I talked to one of my instructors and old friends and family, and I asked for their help and support. I still do not feel I have completely left him behind, because he still tries. But I know what I want, not an abusive relationship. He has not changed and won’t change. “Sometimes I question if I can call myself survivor? But, as a survivor, I want to say something to the victims of dating violence. You deserve a healthier, better, and happier relationship, and you do not even need a relationship to be happy. You are all strong and beautiful. You are a woman, you are a unique person. Accept yourself, accept who you are. Do not accept the woman he tries to change into that you don’t want to be. An abusive relationship is not love. Jealousy is not love. It is violence.” By Isabell Schuster, See the Triumph International Ambassador

Sexual violence is a serious problem all over the world, affecting the survivor’s well-being in different negative ways. Although sexual victimization is highly prevalent among women and recent studies suggest that it also affects men in a considerable proportion, the issue of sexual violence is still not getting the attention and awareness that it should get. A recent study with college students in Germany (Krahé & Berger, 2013) has shown that it is highly prevalent with one out of three women and one out of five men reporting that they experienced sexual activities against their will since the age of 14, the age of consent in Germany. Normally, less than 10% of the incidents are reported to the police, with an even smaller conviction rate. Perpetrators are most commonly intimate partners or friends, making one’s home not the safe place that it should be. However, myths about sexual violence skew the perception of this phenomenon by suggesting that perpetrators are in most cases strangers who attack women in a park when it is dark. Moreover, not only the personal perception but also legislation may be influenced by these myths. For example, until 1997 marital rape was not covered by German law. What is considered sexual victimization in a legal standpoint was debated recently in Germany. For years, survivors had to prove that the perpetrator used physical violence, threat of imminent danger to life, or took advantage of a situation where the survivor was at the perpetrator's mercy. A ‘no’ was not sufficient. But a few weeks ago, the German parliament passed a new law, clarifying that ‘no means no’. Women’s organizations put efforts for years to change this law but especially recent events and developments in Germany have pushed the topic into the spotlight. First, there was a wave of attacks, including sexual violence, at New Years Eve and second, a case of non-conviction became a high media presence since there was a video of the incident where non-consent was expressed. This prompted a campaign for a law reform ‘no means no’. Finally, a few weeks ago the law passed with a huge number of MP in favor for this vote, meaning a big step forward for German law, society, and especially survivors. Cited work: Krahé, B., & Berger, A. (2013). Men and women as perpetrators and victims of sexual aggression in heterosexual and same-sex encounters: A study of first-year college students in Germany. Aggressive Behavior, 39, 391–404. doi:10.1002/ab.21482 By Adah Mbah, Executive Director Mother of Hope Cameroon and See the Triumph International Ambassador

Mother of Hope Cameroon-Mohcam, has been embarking on ending the stigma around intimate partner violence in Cameroon since March 2015 in partnership with See the Triumph. Fighting violence against women and girls is a permanent concern in our Head of State, His Execellency; President Paul Biya’s planning for a sustainable future within the framework of his major accomplishment policy. Cameroon is a bilingual country with a population density of about 23.3 million, and more than 50% of its population is dominated by women. Both women and men suffer from intimate partner violence, but the torture is more severe and common for women than men. This is evident from the work of Mohcam on intimate partner violence through women’s groups in Cameroon. Intimate partner violence extends to affecting victims’ relationships in the communities in which they belong negatively. They are stigmatized in church, women’s gathering, within their families and social groups, and at their job sites. Intimate partner violence makes women in Cameroon feel rejected, and a lot of them have died because of intimate partner violence. Intimate partner violence also has a negative effect on the country’s growth and development because women form a bulk of the country’s population. The stories of two women whom MOHCAM have worked with Mohcam make explicit what people need to know about intimate partner violence in Cameroon. The first woman is a teacher in her mid-30s. She has two children and is legally married to her husband, whose other children she also takes good care of. She has been abused for many years now, including physical, psychological, and economic abuse. Her husband has forced her out of the house that she contributed financially to, and she sought our help at Mohcam to ask us to intervene in the situation on her behalf. The second woman has three young children and was abandoned by her husband after he was violent toward her for a long time. In addition to reaching out to us at Mohcam, this woman has also taken the case to many legal institutions, like the customary court, bailiff, and judicial police, but he has not followed the requirements of these legal institutions. In particular, he has not paid monthly child support for many, many years. This is a serious issue, and Mohcam has been following up to ascertain the facts, and lawyers have been brought in to handle the case. These are typical cases amongst thousands in Cameroon. Intimate partner violence in Cameroon has grim consequences for women in their daily lives, especially in the African context. Many women have bought land properties in Cameroon, and today these assets are owned by their husbands as a result of intimate partner violence. In our country, this is slowing women’s growth and progress and is a violation of women’s rights. For these reasons, Mohcam remains dedicated to educating and advocating for women and girls, as well as creating opportunities to build future women leaders. We believe in the values of our mothers and want to give back as mothers in the development of the lives of women and girls living with stigma and pain. By N. Büşra Akçabozan, See the Triumph International Ambassador

What is intimate partner violence? The definition of intimate partner violence (IPV) should be clear in our minds. The term "intimate partner violence" describes physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive acts) by a current or former intimate partner. An intimate partner can be a spouse or a partner with whom you have been dating, cohabiting, having a sexual relationship, and/or sharing an emotional connectedness. As the description indicates, there are various types of IPV, although you might first think of ‘physical violence’. However, there are other types of IPV, which include: sexual violence (sexual acts committed against the victim without his/her freely given consent), stalking (repeated and unwanted behaviors and attitudes toward the victim who does not want to be exposed to, e.g., unwanted phone calls, emails, following, sneaking into the victim’s home, school, workplace and making threats etc.), and psychological aggression (harming and/or controlling the victim emotionally and psychologically, such as humiliating, excessive monitoring, and limiting behaviors). Have you ever thought of these types as types of IPV before? According to my observation and research, primarily physical violence followed by sexual violence has attracted attention in Turkish culture (in the literature, in daily life, and the news); however, stalking and psychological aggression have recently become a current issue. What is important for people to know about IPV that occurs in Turkey? Both in Turkey and across the globe, we know that women are at a significantly greater risk of IPV than men. According to 2014 statistics in Turkey (Ministry of Family and Social Policies, 2015), 4 out of every 10 women have been physically abused in Turkey. Among them, three fourths have been abused by their spouse. Most women who were victims of murder were murdered by their spouses. In general, sexual violence occurs with physical violence; 12% of women reported sexual partner violence, and 27% of women reported both physical and sexual partner violence. In terms of psychological violence, 44% of women reported that they have been psychologically abused by their partners for any period of time. All across Turkey, approximately 3 out of every 10 women have been stalked insistently. The health of Turkish women impacted by IPV has been affected in a negative way as a consequence of physical and/or sexual abuse. Some people believe in myths about IPV, such as “IPV occurs only between people who are not well educated” and/or “who are living in rural areas.” However, these myths are NOT TRUE. The percentage of physical violence in rural areas was 43%; however, in urban areas this percentage was high as well at 38%. Further, among women who are highly educated, 3 out of every 10 women reported being physically or sexually abused by their partners. Hence, based on the statistics, women in different age groups, educational levels, and socio-economic statuses are all under threat. 48.5% of women indicated that they could not tell anyone about the violence they were exposed to, and only 11% of women informed government agencies, which means that women have been struggling with violence ALONE. What can we learn from these numbers and percentages? Unfortunately, these numbers and percentages reveal how frequently IPV occurs and how lonely the victims of IPV are in Turkey; however, we know that the story is not much different across the globe. This information is important for us to be aware of the situation in Turkey in terms of IPV and to question ourselves, our partners, and our culture. We are NOT culture-free; however, we can be aware of the cultural and social norms we have been taught since we were born. For instance, I sometimes observe that individuals try to legitimize and justify IPV in their daily conversations, attitudes, behaviors, especially when it is used by men. This also happen in school systems, in the media, and even in the courts. We have to object to any behavior that encourages IPV violence and any excusive attitudes toward violent acts. We need to encourage survivors to tell their stories and be there for them to help them overcome the partner violence they were exposed to. We should develop supportive environments, provide more resources for victims of IPV, and start raising awareness about the importance of this issue, first in our own culture and then around the world. We should remember that every person around the world deserves to have a functional, nonviolent, and healthy relationship! Reference Ministry of Family and Social Policies (2014). Summary report of the research of domestic violence against women in Turkey (Türkiye’de Kadına Yönelik Aile İçi Şiddet Araştırması). Retrieved from http://www.hips.hacettepe.edu.tr/KKSA-TRAnaRaporKitap26Mart.pdf By Angiemil Pérez Peña, See the Triumph Guest Blogger Walking into the local shelter for someone experiencing domestic violence can be hard. Reaching out for help to the local community agency or navigating the local resources can be overwhelming for a local resident, but how much more daunting is it to navigate for an immigrant women? When seeking help for an abusive relationship, many immigrants experience increased difficulties and additional barriers for individuals in this group to exit their abusive relationship. The existing research tells us that documented immigrants, and even moreso for undocumented immigrants, are much less likely to report domestic violence to the police, compared to their non-immigrant counterparts.(1) Some of the barriers that immigrants experience when they do reach out for help include lack of fluency or speaking the dominant language, immigration status, financial dependency on their partners, lack of knowledge about their legal rights, not desiring to perpetuate negative stereotypes of their culture, and the lack of existing culturally appropriate services. Additionally, abusers may exploit these vulnerabilities to keep the victim in the relationships. When you consider the threats immigrant victims may receive--such as the abuser keeping their legal documents, threatening to call immigration and take away the children, refusing to file immigration papers, and denying access to legal documents, to name a few--you begin to understand the added difficulty for immigrant women leaving domestic violence. Changing the accessibility of resources for immigrant victims of domestic violence will take the involvement of the entire community. We need to continue to reinforce the idea that domestic violence is a social problem, and we all have to take part of the solution. This includes educating members and leaders of vulnerable communities to think of more social justice solutions. If you’re in a position to help an immigrant who is experiencing an abusive relationship, consider the following suggestions. First, help the person to consider ways to promote their safety, whether or not they leave the relationship. Second, think of the cultural strengths that individuals belonging to collectivistic culture may have, such as social support and having support family members that could help to protect them from an abuser. Third, educate yourself on specific resources available regarding immigration, protective laws such as VAWA, and additional local community resources. Fourth, make every effort to provide services in the native language or work with interpreters who are trained to understand domestic violence. Lastly, strive toward becoming culturally responsive to the needs of underserved populations. Working together, we can foster communities that offer support and safety for immigrant survivors of domestic violence. Reference: 1: Sokoloff, N. J. (2008). Expanding the intersectional paradigm to better understand domestic violence in immigrant communities. Critical Criminology: The Official Journal of the Asc Division on Critical Criminology and the Acjs Section on Critical Criminology, 16, 4, 229-255.  Angiemil Pérez Peña is a graduate student at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro studying Couple & Family counseling. By Michelle Vann Horton, See the Triumph Guest Blogger

Places of worship are often viewed as safe havens, a refuge for those in need. This perception has been no different for many immigrant victims who suffer from intimate partner violence. Many times, immigrants reach out to their religious leaders first before seeking professional sources of support. This sounds like a good idea, since religious institutions play a vital role in helping immigrants maintain their cultural identity and stay connected to others. Can we assume that religious leaders who shares a similar cultural background would be empathetic to immigrant victims of intimate partner violence? Unfortunately, in many cases, this is not what happens. In reality, many religious leaders react negatively or are unsupportive to victims of abuse. There are many reasons this may happen. First, many religions promote a harmful patriarchal point of view, which promotes male domination over women. From this lens, gender norms are established where sexual inequality is accepted and upheld in families throughout generations. Second, group-oriented cultural ideologies often prioritize the advancement of the community, family unit, or marriage over the wellbeing of the self. In addition, cultural definition and perceptions of intimate partner violence can vary greatly, and in many immigrant communities, these issues are not even acknowledged. Together, these cultural views can contribute to the negative reactions religious leaders may project as they silence victims or blame the victims’ behavior as cause for the violence (i.e., victim-blaming). Leaders may relay the message that it is the victims’ responsibility to stop the violence and imply that victims’ abuse results from their failing in their relationship with God. It is important for immigrant victims of family violence to surround themselves with multiple sources of support, especially people and organizations that have expertise with helping people impacted by violence and abuse. I know this may be easier said than done, especially with the overwhelming barriers immigrant populations face daily, like language barriers, discrimination, adjusting to mainstream culture, and lacking knowledge about U.S. laws and available support systems. Due to these barriers, it is vital that community agencies have the training and the staff needed to meet the culture-specific needs of the growing immigrant population in the U.S. Moreover, it is imperative that domestic violence agencies also connect with religious institutions and leaders that serve immigrant communities in order to become more proactive in removing the stigma associated with family violence, especially within places of worship. As agencies partner with religious institutions, religious leaders can increase their competence in supporting victims and survivors, as well as create community norms that promote safe relationships and families. In addition, prevention and educational programs can be implemented that honor and respect cultural norms while reframing the ideals of what a healthy marriage and family looks like. Ultimately, religious leaders have the power to confront controversial issues like family violence in their preaching and in their teachings. The ability to take a stand against family violence while at the pulpit sends a direct message to congregants that promotes survivors’ safety and holds abusers accountable. By HM Humphrey, See the Triumph Guest Blogger  H.M. Humphrey recently graduated from UNCG with a masters in Counseling. She is passionate about working with couples and families, and feels the importance of engagement and advocacy for the promotion of social justice in the community. References

By Allison Crowe, See the Triumph Co-Founder

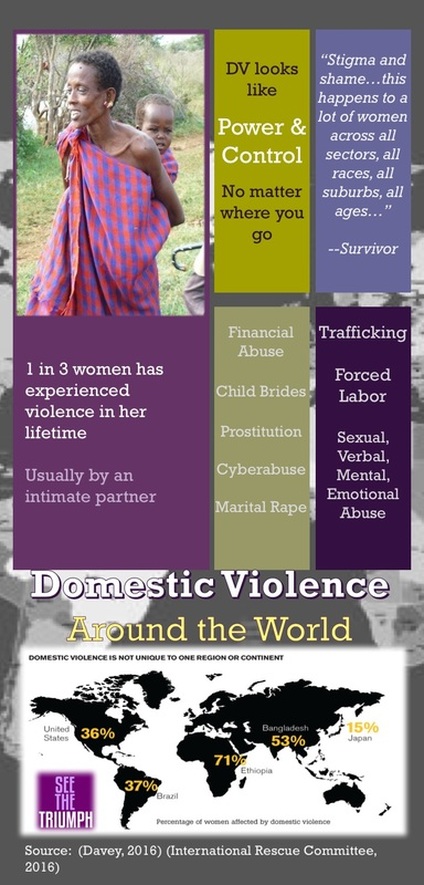

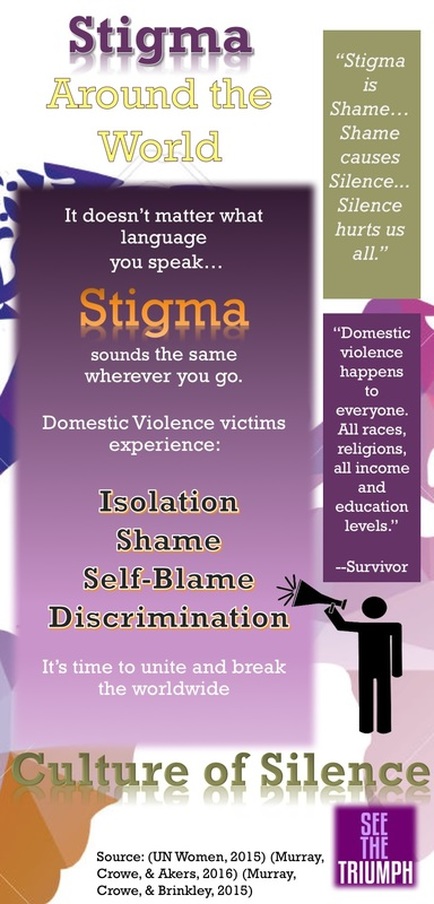

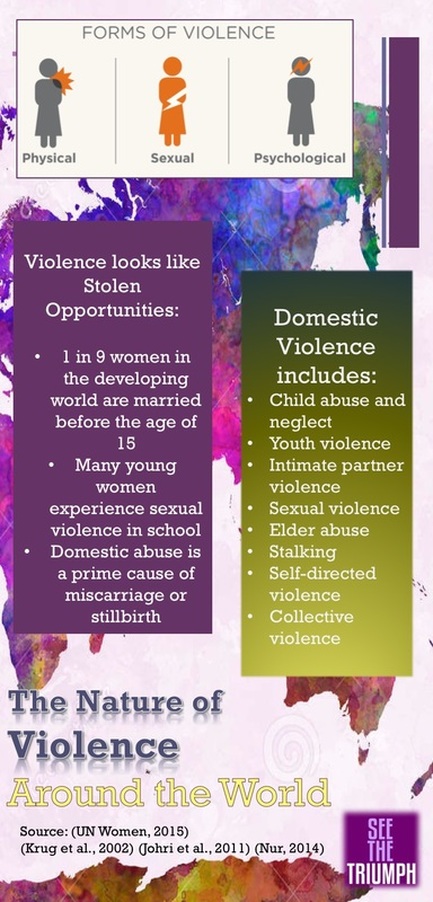

This month, we are focusing on “Seeing Triumph Around the World” and spotlighting some of our very important international ambassadors who make up our newest See the Triumph initiative, the International Ambassadors Program. We will pay special attention to international issues this month because we firmly believe that violence is a global issue, and that learning from each other will only help all of us as we work together to end domestic and intimate partner violence around the world. According to the World Health Organization, 1 in 3 women worldwide have experienced some form of intimate partner violence. This statistic is upsetting. We also know that the stigma that surrounds intimate violence in so many cultures is a large part of why these numbers are so high. Stigma because some believe that domestic violence is something that occurs “behind closed doors.” Or stigma because a victim believes that she or he somehow deserved to be abused. Or stigma because a victim feels embarrassed or ashamed that he or she did not leave the relationship sooner. Given these sorts of facts and complexities, how do we maintain the belief that we can work together to end the stigma of intimate partner violence? The answer is, through you. All of you out there have a story to tell. A story about how you struggled. A story of how you still might be struggling. A story of how you made it out alive, or how you have since helped someone else. The way we can continue to overcome intimate partner violence, and stamp out the stigma that surrounds it is by hearing from you. We encourage you to tell us your story. We have heard from nearly 500 of you who have wanted to share your story – we invite anyone else who wants to participate to do so here: http://www.seethetriumph.org/participate-in-our-research.html Help us continue to talk about not only surviving but triumphing over intimate partner violence and the stigma that surrounds it! These are global issues, and this month, we want to hear from all of you. Remember, it’s you who can make the difference for someone else – in your own community or around the world By Christine Murray, See the Triumph Co-Founder

The Rio Olympics recently brought the world together around athletics, and global awareness always peaks around Olympics seasons. But what about at other times? When we don’t have daily reminders about the connections between our own communities and the rest of the world, how much time do we spend reflecting on how are local communities are interlinked with others in countries across the world? This month, we’re doing a special theme for See the Triumph to highlight international issues related to the stigma surrounding intimate partner violence. Of course, we won’t have the opportunity to address every single nation and culture around the world. However, we hope that throughout the month, we’ll encourage members of our community to consider how understanding international issues can change our thinking about intimate partner violence, culture, and the experiences of survivors. In the beginning of 2016, we launched our See the Triumph International Ambassadors Program. We were thrilled to partner with Ambassadors from a diverse group of countries who are working with us to help expand our See the Triumph to end the stigma surrounding intimate partner violence and develop supportive resources for survivors around the world. You’ll hear from several of our Ambassadors this month and learn about their unique perspectives on intimate partner violence in their countries. At See the Triumph, we believe in the “Think Globally, Act Locally” approach. The truth is what happens around the world, in communities far away from our own, impacts us. This is true more today than ever, with global migration patterns changing all the time. For this reason, we’ll also address immigration issues this month as part of this series. Immigrants often face added levels of complexity and stigma when they seek help if they are being abused in a relationship, and it’s important that we consider ways to make community services and resources more accessible to immigrant survivors. Beyond immigration issues, intimate partner violence that happens across the world affects us for the very important reason that safe, healthy relationships are a basic human right. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” It’s important we work toward ending violence in our own communities, but we can’t rest until everyone, everywhere, is free from violence and oppression. We hope you’ll join us in this journey to explore stigma, intimate partner violence, and stigma around the world. Throughout the month, please share your comments and your own experiences to help move this dialogue forward! |

Archives

July 2024

CategoriesAll About Intimate Partner Violence About Intimate Partner Violence Advocacy Ambassadors Children Churches College Campuses Cultural Issues Domestic Violence Awareness Month Financial Recovery How To Help A Friend Human Rights Human-rights Immigrants International Media Overcoming Past Abuse Overcoming-past-abuse Parenting Prevention Resources For Survivors Safe Relationships Following Abuse Schools Selfcare Self-care Sexual Assault Sexuality Social Justice Social-justice Stigma Supporting Survivors Survivor Quotes Survivor-quotes Survivor Stories Teen Dating Violence Trafficking Transformative-approaches |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed