|

5/18/2014 Fathering With The ForceBy Sherrill W. Hayes, Associate Professor and Director of the Master of Science in Conflict Management at Kennesaw State University See the Triumph Guest Blogger As a boy, I spent more time than I care to remember playing war and other violent games. I don’t know how I managed to squeeze in my homework among the lightsaber battles with shadow Darth Vader, shooting invisible Nazis from treetops, and bodyslamming pillow Andre The Giant. As I recall the amount of mental and physical energy I exerted in organizing my GI Joes in neat columns and planning the next epic rebel attack on the Death Star, I can only marvel at the other things I might have done. Now as a parent and a conflict management scholar, I find myself questioning my children’s exposure to they very things that fully occupied my time when I was a kid. No matter my actions, I feel I let myself down almost daily. I look around the house and see my children watching things and playing games that my inner social justice activist finds utterly inappropriate. My daughter watches shows that reinforce all the wrong gender stereotypes and constantly squabbles with the neighborhood girls in pre-cliqueish behaviors. My son has a blue plastic tub box that contains swords, archery sets, lightsabers, magic wands, and countless other implements of destruction. As I stand there in that moment, I tell myself “these things didn’t do me any harm”, then the news interrupts with an expose on cyberbullying and a breaking story of another campus lockdown. That is when I feel the need to shelter them from the horrors of this world. “The Force is…an energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us and penetrates us. It binds the galaxy together” The truth is that our jobs as parents cannot be considered through a snapshot of one moment. We are often our own worst critics, ignoring the good things we do and forgetting that we are not doing this job alone. Parenting is less about our actions and more about our interactions with our children, our co-parents, and the communities in which are children present. When we ignore these relationships, we forget that our children developing the skills they need to understand the complexities of the world from their experiences in these relationships. This is when I realize that I got more from Star Wars than lightsaber battles and a garage full of toys, I learned about The Force. “Fear leads to anger, anger to hate, and hate is the path to the Dark Side…” When Yoda is training Luke on Dagobah in “The Empire Strikes Back”, he sends him into “the cave”, where Luke must face his deepest fear. When Luke sees Darth Vader walking towards him he lashes out, beheading Vader in the process. The fallen mask then explodes and Luke sees his own face. A poignant, if violent, scene that teaches us that when we react to a situation with violence we often become the thing we fear the most. As a conflict management scholar, I know this is the nature of how disputes escalate and is the root of the most intractable forms of identity-based conflicts. It is also a scene that my son fully comprehended when he first saw it at 4 years old. My wife and I decided early on that rather than trying to directly shape our children into the people we wanted them to be through our own preferences and interests, we were better served by following their lead and look for the lessons that we can teach them in those interests. This means being observant, thoughtful parents who are prepared to talk to our children about violence they witness in ways that make sense to them. By acting as filters and guides to them rather than monitors and deprivers, we are better able to help them find their own balance. To be fair, my son asked to watch Star Wars because he loves his Dad and knows I love Star Wars, but watching it together has provided me many opportunities to see how he sees the world and help him. When do things together, he knows that I am also interested so we find opportunities to talk about the things that may be confusing, scary, or difficult. At 4 ½ my son explained to me the inner turmoil of Darth Vader as he threw Emperor Palpatine into the pit, which resulted in the ultimate reconciliation of a dying Anakin Skywalker with his son Luke at the end of “Return of the Jedi”. When I asked my son what he thought of this emotionally complex story line, all he said was, “He did it to save his son, because love is The Force Dad”. So the next day when we wanted to fight me with a lightsaber I knew that there was more to his war play than just the battle, I knew he understood “the true nature of the Force”. I have come to believe that building those relationships with and for my family are the most powerful weapons we have to prevent violence in our communities, just like Obi Wan and Yoda said they were. For more on parenting, war play, and Jedi conflict resolution, see… http://www.naeyc.org/files/tyc/file/Levin_1.pdf http://www.scholastic.com/parents/resources/article/parent-child/war-play-bad-kids http://www.ppu.org.uk/chidren/politics.html http://www.mediate.com/articles/hayesS2.cfm  Sherrill W. Hayes, Ph.D., is Associate Professor and Director of the Master of Science in Conflict Management at Kennesaw State University in suburban Atlanta, GA. In his career, Dr. Hayes has taught preschool, worked as a family and child custody mediator in the UK and US, designed and evaluated conflict resolution programs for governments and non-profits, and trained to a wide array of business, non-profit, and education professionals. He has published research, received grants, and taught university courses related to child development in cultural contexts, family and community conflict resolution, sports as a peacebuilding tool, and creating humanitarian space for refugee resettlement. He is a registered neutral in the State of Georgia, a member of the Association for Conflict Resolution (ACR) and the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts (AFCC). To read more of his work and connect with him go here: https://kennesaw.academia.edu/SherrillHayes 5/17/2014 Parents as Models of NonviolenceBy Sara Forcella, See the Triumph Contributor

We expect parents to teach children how to walk, talk and read, but do we ever think about what parents’ intimate relationships teach their children? For better or for worse, parents play a large role in teaching their children how to behave and function within the context of intimate relationships. If you have been following our blogs at See the Triumph, than I am sure by now you know that intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious, preventable public health concern that affects millions of people around the world. IPV is serious-- it can lead to low self esteem, anxiety, depression, homelessness, physical injuries and even death. However, it can also be prevented! In order to help prevent IPV we must understand some of its underlying causes. There are many different theories of what fosters the development of intimate partner violence, one of these is the Social Learning Theory. This theory suggests that intimate partner violence is a learned behavior. Children learn violent patterns of behavior at home or from our culture, which models, rewards and supports violence against others (Wolfe & Jaffe, 1999). In much the same way that children learn language and decision-making skills, they may learn how to abuse others (Wolfe & Jaffe, 1999). Therefore, parents have a major responsibility to teach their children how to act in intimate relationships. When family members or other role models use abusive behaviors, children begin to model these behaviors. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence states that “witnessing violence between one’s parents or caretakers is the strongest risk factor of transmitting violent behavior from one generation to the next.” Children also learn these behaviors through reinforcement and punishment (Wolfe & Jaffe, 1999). For instance, when a parent slaps their child when he or she does something wrong, this child may learn that it is appropriate to lash out against others to punish them. Teaching children about IPV is a continuous process. When adolescents begin dating, parents can encourage them to be quality and caring partners. It’s important to teach teens what is and is not acceptable in dating relationships. Teaching children and teens the skills necessary to foster and maintain a healthy, non-violent, intimate relationship is crucial for their well being! Here are some suggestions for helping to prevent your child from becoming a victim or perpetrator of IPV: Provide Them with Safe Homes: Children who live in homes where IPV occurs are more likely to become a victim or perpetrator even if they are not being abused. Witnessing a parent being abused is traumatic--it can also teach children that abuse is an acceptable way to deal with partners. Model Nonviolent Behaviors: Teach your children how to deal with stress and anger. Just as you would show them how to brush their teeth, show them how you handle conflict in constructive ways. Teach them how to communicate with others without using physical, emotional, or verbal abusive. Speak to and treat your partner, children, and others with respect and tolerance. Fight Gender Stereotypes: In today’s society, children face much pressure to fit into typical gender stereotypes--girls are told to be sensitive and quiet, while boys are told to be aggressive and strong. Gender is socially created; therefore, not all girls and boys will act these specific ways. It’s important for parents to encourage both their boys and girls to be caring, compassionate members of society. Putting strict labels on how young men are expected to act sometimes reinforces the ideal that to be man they have to be aggressive or violent. Ideologies like this reinforce that violence against women is acceptable. Speak Up: Talk to your children about IPV, and don’t assume that they are too young to understand what it is. Teach your children that abuse is never OK. Keep Lines Of Communication Open: Make sure that your children feel safe and supported. Encourage them to ask questions and speak to you when they are concerned or confused about something that’s taking place in their or a peer’s relationship. Be Supportive and Loving: Make your child feel loved and proud of who they are! Support and encourage them to develop into creative, caring, confident and compassionate individuals. References Wolfe, D. A., & Jaffe, P. G. (1999). Emerging Strategies in the Prevention of Domestic Violence (3rd ed., Vol. 9 ). By Sara Forcella, See the Triumph Contributor

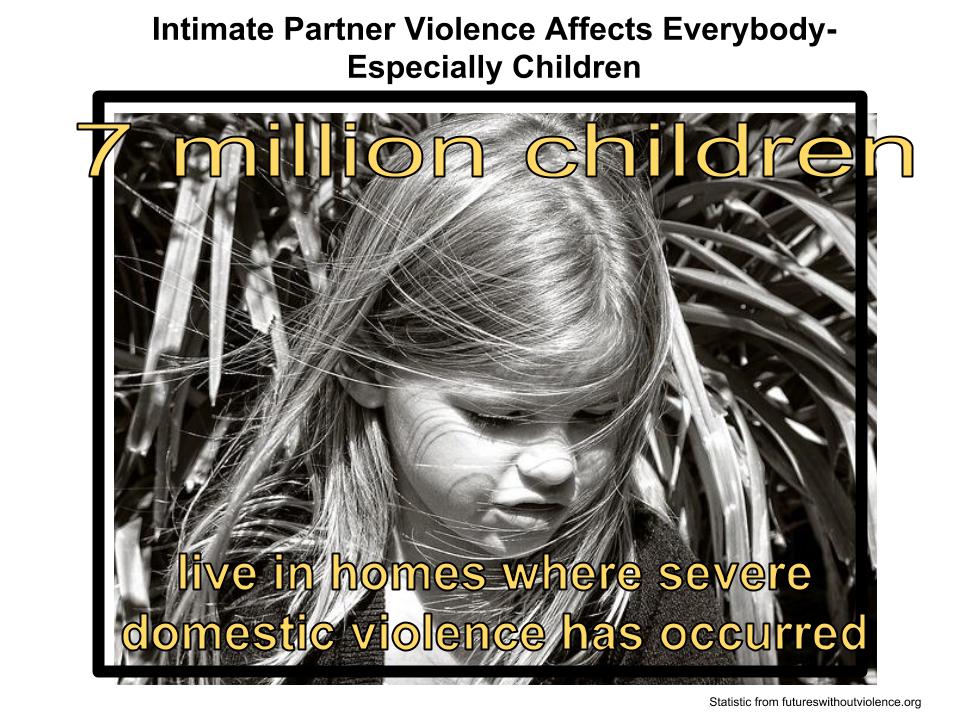

There are a number of concerns for children who are raised where intimate partner violence (IPV) is present. Even if a child is not physically abused, there are typically severe consequences that coincide with witnessing a parent being abused. Children’s brains are continually developing; therefore, being in homes where IPV is present can be cognitively, behaviorally, developmentally and emotionally stunting. IPV affects children in a multitude of ways; the Child Welfare Information Gateway states that children who deal with violence at home face issues such as increased levels of anger and fear, poor social skills, poor relationships skills and a low self-esteem. Being raised in a home where partner violence is present can even be an indicator for future alcohol/drug abuse as well as juvenile delinquency. Witnessing violence between parents at a young age is also one of the main reasons that violent behavior is passed along from one generation to the next. Children who witness IPV in their homes, especially boys, are also more likely to be abusive to their own partners and children in the future (Source: The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence). Considering the negative effects that intimate partner violence has on children, our society needs to be aware that 7 million children live in homes where severe domestic violence has occurred (Source: futureswithoutviolence.org). This is an important statistic to remember, considering that 30-60 percent of perpetrators of IPV also abuse their children (Source: The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence). Even if a child is not being physically abused, witnessing the abuse, or simply seeing its aftermath is detrimental to children and is something that no child should have to worry about. All children deserve to live in a safe and healthy environment. If you suspect that a child is being abused or living in a home where domestic violence is occurring, please take the first step and report it to your local law enforcement or child protective services agency. Simply being aware and raising your voice can save a child’s life. By Monika Johnson Hostler, Executive Director of the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault

See the Triumph Guest Blogger I still remember it like it was yesterday. It was a beautiful May morning, the day the doctor would confirm it was a girl. The moment I knew I was pregnant I also knew it was a girl. When the doctor confirmed it, one tear slipped from the corner of my eye. I knew that single tear held multiple emotions. I felt sheer joy and elation to be able to give what my mother gave me: the power to be an individual, a strong women. I also realized I was going to give birth to a daughter in a violent world. A world that is not only violent, but silently accepts the violence. However in the same 60 seconds I also realized I had spent the last ten years dedicated to ending violence again women, girls and our most vulnerable. So yes, I was capable of raising a daughter, and yes, she too could survive and thrive because I still have hope. Hope that we are laying the foundation, building the infrastructure needed for a world of peace, love, and all that good stuff. As it turns out that was the first of many moments of conflicting emotions about my role as a parent and as a womanist and they still persist today, nine years later. The internal conflict begin as we thought about names, bought clothes, chose paint, you know all the stuff most new parents enjoy. Now, I am not saying I didn't enjoy it, but I am saying doing this work makes most of us hypervigilant about everything. This experience was sobering in so many ways because all the research I had touted about raising girls and boys with equity and equality included ideologies like: use neutral colors, neutral language and let them choose their own path. That went out the window the first time I saw an adorable pink, ruffled dress that my princess had to have. To most people, this doesn't seem strange but my sisters in the work will understand that pink and blue are gender-prescriptive stereotypes that contribute to beliefs that girls are less than boys and perpetuate violence against girls. I bought the dress and many more like it, but not without the struggle. In the months to follow that I spent on bed rest, I didn't read any parenting books. Instead, I spent the time in my head. I needed to reconcile what was going on for me, as an advocate who was soon to be a mother. I concluded that as humans, we are complex and multidimensional and can hold many ideologies and beliefs. Being rigid in my beliefs worked when I was only responsible for myself but parenting made it clear to me that I would learn to be flexible. I also recognized there are many roads that lead to ending violence against women and children; not all roads are one-way. The pink dresses were not a one-way road to condoning violence. Eight and a half years later, I can see the self-evaluation and reconciliation were worth it. I am still a strong passionate advocate that believe we will end violence against women and children. Most importantly, I remember the key is prevention, and that means investing in children. Violence prevention is about culture and norm changes. Making sure ALL children are safe, healthy and loved is an investment in a future without violence. The moral of the story isn't about my daughter being a princess in pink, but it is about the reality of being a parent. Parenting is challenging and requires constant self-assessment. I still don't have an answer on how we raise children in a world full of messages that perpetuate patriarchy and violence. But, below are a few things that help me in holding both roles while maintaining my sanity.

I can only hope that my daughter will see my decisions as an investment and that she too will be a change agent. Parenting and ending violence against women and children is everyone's responsibility and it begins with PINK: Protecting, Investing and Nurturing ALL Kids. About the Author: Monika Johnson-Hostler is the Executive Director of the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Prior to coming to NCCASA, Monika worked at the local rape crisis center in Scotland County as the Crisis Intervention Coordinator. Monika has been an activist in the social justice movement for over 15 years. In that time, she has presented on the issue of sexual violence to numerous communities including the Joint Task for the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Military Academy subcommittee. Johnson-Hostler serves as the board chair of the National Alliance Ending Sexual Violence (NAESV), one of the policy entities responsible for the passing of the Violence Against Women Act and securing over $420 million for violence against women work across the country. Monika was appointed by the Obama administration to serve on the National Advisory Committee on Violence Against Women. By Kris Macomber, PhD See the Triumph Guest Blogger As a parent committed to non-violence, I know that the first few years of my son’s life are a special, sacred time. I know that for a brief period of time, he will know only my version of the world—a world where peace, love, safety, and self-freedom overflow. A world where all forms of violence are non-existent and where cultural definitions of “masculinity” are relatively inconsequential for him. I am happy knowing that he will live in this special world, even for just a few years. I know that, eventually, the violent culture he was born into will show him a different version of the world—a world where domestic and sexual violence is normalized and widespread, and where boys and men are socialized to be complicit with it, or at the least, consider it unremarkable. As a sociologist, I study and teach about things like childhood gender socialization, the construction of “masculinity” and “femininity” in mass media, and gender-based violence (including domestic and sexual violence). Although these may seem like distinct societal trends, it is my job to identify how patterns of daily life connect them. That is, if we place violence against women at the end of a continuum, we would place childhood gender socialization (i.e. telling a boy to “man up,” “stop acting like a girl,” and marketing toy guns to boys) at the beginning of the continuum. Then, from there, we would place many other patterns across the continuum (the sexual objectification of girls and women, victim blaming, the stigmatization of victimization, and homophobia and heterosexism, to name a few). So, as a parent and as a sociologist, I am tuned-into this continuum and to how Kaden, my son, who is 4 years old, is experiencing and making sense of different parts of it. I am concerned about how he is confronted, again and again, with media images and other forms of consumer culture that depict boys and men as dominant and aggressive, while depicting girls and women as compliant and ornamental. We see this in everything from children’s books, to television shows, to advertisements, to movies, to computer games. This is the world he has inherited. Raising Full Children As Kaden navigates the world around him, I am concerned with how narrow gender expectations and the association between “masculinity” and violence will impact how he thinks of himself, of other boys and men, and of girls and women. If he learns that acting “girly” is supposedly one of the worst things he can do, what is he then learning about the worth and contributions of girls and women? Also, what will he think about people who don’t identify with our rigid gender binary? And perhaps the most important question, what is he learning about the relationships and connections between these groups of people? I want to help my son develop his full human potential, not just the parts of him that match societal assumptions about what it means to be a boy. What does that even mean anyway, to be a “boy?” Shouldn’t we teach our children to strive to be good people, rather than “good boys,” or “good girls?” Doesn’t the latter limit all that they can be? So, as a parent trying to raise a non-violent child in a violent culture, what do I do? I do the one thing I can do. I ask questions. That is, I ask Kaden questions, lots and lots of questions. My hope is that by asking him questions, I can help him develop what I call social literacy—the ability to read and interpret the world around him. I ask him questions about the images he views, about the stories we read together, about the toys he plays with, about the interactions he has with people, and about the feelings he feels. Developing Social Literacy: The Importance of Asking Questions As parents, we help our children learn to do so many wonderful things. We teach them how to ride a bike, to swim, to read, to write, to count, to be polite and kind to others. We can also teach them how to make sense of the social world they live in, and how to think more critically about it. My hope is that if I keep asking Kaden questions, he will eventually start asking his own questions. One thing that asking questions can do is help children develop media literacy skills. Right now, Kaden is young enough that I can monitor and control most of the media he consumes. However, this will get harder as he gets older and becomes more independent. He will be exposed to more violent imagery and to ideas that support the use of violence as a way to handle conflict, especially for boys and men. If he learns to ask questions about the media he consumes, and if he learns to see the media through a more critical lens, he might be better able to assess and analyze it, rather than simply accept it for what it. Some questions I have asked him are: “Can girls and women be superhero’s too?” And, “Why do you think the people who make movies always make a “bad guy” character? Asking questions can also help nurture children’s emotional expression, which for boys is especially important because they will face pressure to suppress their emotions. I frequently ask Kaden questions like, “How does that make you feel?” And, “When she hurt your feelings, what was it that made you feel bad?” Being able to articulate their feelings is critical for children’s emotional development and well-being. It also takes practice. Asking questions is one way to help them practice I also think it’s important to ask questions that nurture their capacity for empathy, which I try to do by asking him questions about how others might feel. For example, when we were at a playground one afternoon, Kaden was playing with a group of older children and one of the older boys said, “Let’s make a fort, but there’s one rule. No girls allowed.” I asked Kaden afterwards, “If you were a girl, how do you think that rule would make you feel?” He said, “It would hurt my feelings because it’s not very nice.” We talked about it some more and I introduced the concept of fairness to him. I wasn’t sure if he understood what I meant, but it was a start. A few months later, a similar situation occurred. We were at the same playground and, again, an older boy said, “Come on, let’s go on the merry-go-round! Just the boys.” Kaden said, “That’s not fair. Everyone come on the merry-go-round.” I watched with pride as those children spun around in circles. By holding space for him to engage his feelings, and by nurturing his capacity for empathy, I hope he continues to develop a vocabulary for discussing his emotions, and the confidence to do so. Preparing them for the Riptide When I think about the powerful influence that culture has on our children, especially media culture, the image of a riptide always comes to mind. The better prepared our children are to confront the riptide, the better their chances are of not being carried out to sea. I certainly don’t have all the answers. But, what I do have is a steady supply of questions. I will continue to ask Kaden questions to help him cultivate good social literacy skills and to help him develop his full, human potential. It is my hope that as he grows older, he matures into the loving, peaceful, and empathetic person he is at this very moment.  Author Bio: Kris Macomber, PhD, is a sociologist who specializes in gender-based violence, childhood victimization, gender in the media, applied and public sociology, and community-based research. Kris earned her PhD from North Carolina State University, where her dissertation research examined men’s growing involvement in the anti-violence against women movement. Kris’s publications span a variety of academic and applied outlets, such as: The Sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a Modern Catastrophe, Feminist Teacher, The Journal of Popular Culture, and Teaching Sociology. She is a passionate anti-violence activist and educator who loves teaching students about sociology and social justice issues. She is currently an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Sociology at Meredith College, in Raleigh, NC. Kris gives talks and presentations on the following topics: “Men As Allies: Mobilizing Men to End Violence Against Women,” “Male Privilege in Violence Prevention Work,” “Practitioner-Researcher Collaborations,” “Gender in the Media,” “Gender Inequality,” and “What is ‘Rape Culture?’ You can also visit Kris's Everyday Sociology Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Everyday-Sociology/245523538906269?ref=hl# |

Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll About Intimate Partner Violence About Intimate Partner Violence Advocacy Ambassadors Children Churches College Campuses Cultural Issues Domestic Violence Awareness Month Financial Recovery How To Help A Friend Human Rights Human-rights Immigrants International Media Overcoming Past Abuse Overcoming-past-abuse Parenting Prevention Resources For Survivors Safe Relationships Following Abuse Schools Selfcare Self-care Sexual Assault Sexuality Social Justice Social-justice Stigma Supporting Survivors Survivor Quotes Survivor-quotes Survivor Stories Teen Dating Violence Trafficking Transformative-approaches |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed